Information

Besançon BM MS 0054, f. 011v

Psalter c. 1260, Germany

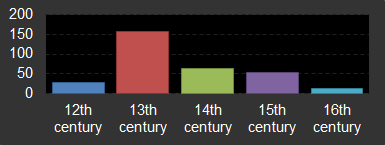

Aquamanilia are figured vessels used for ceremonial and hand cleansing purposes. They are typically cast from a copper alloy. These items were produced in large numbers in Europe from the 12th through 15th century, peaking in the 13th century and finding a place at the tables of nobility and in houses of worship.

Sample

The sample contained on this website from which the following statistics were derived contains 322 aquamanilia. It has been restricted to those from western Europe (the Middle East is also a production center) that were cast in metal (pottery aquamanilia exist) in the medieval period (no reproductions or later period pieces inspired by medieval examples). 298 are independently documented to a region or city, and 257 have at least one documented dimension. All but 8 have been independently dated.

Medium & Method

Aquamanilia are cast via the lost-wax method, where a wax positive is melted away leaving a cavity where the metal is poured. All extant metal aquamanilia are made with some form of copper alloy, often brass or bronze. The most valuable were made from silver. None of these survive today, all probably melted down. Aquamanilia were among the first hollow items to be cast during the medieval period.

Form

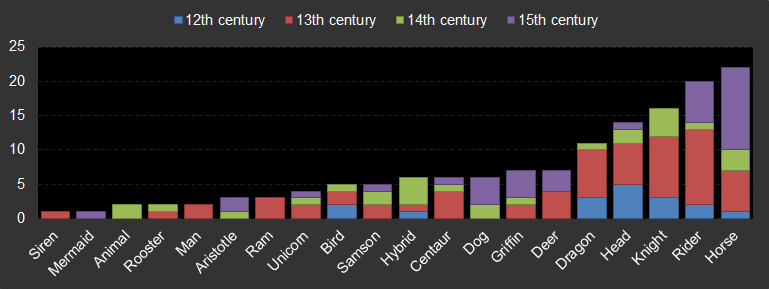

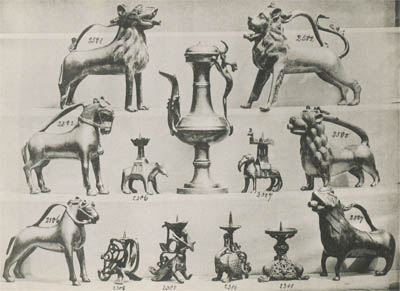

Aquamanile forms are varied but always that of a creature. Animals, particularly those with powerful symbolism, were the most popular. Of these, the lion dominates, composing a full 55% of the sample documented on this website. Next most popular are variations on a horse theme - men riding horses, including knights, and horses alone - 40% of non-lion aquamanilia. The full range and popularity of forms is charted in figure 3. The rarest forms are the mermaid (a single example held at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg) and the Siren (a single example held at the Kunstgewerbemuseum Berlin). The figure excludes lion forms (except those depicting Samson’s encounter with a lion) in order to highlight the other forms. The lion form was consistently produced from the 12th through 16th centuries. The 12th century, when the aquamanile was becoming popular, naturally contains the least variation on forms.

Size

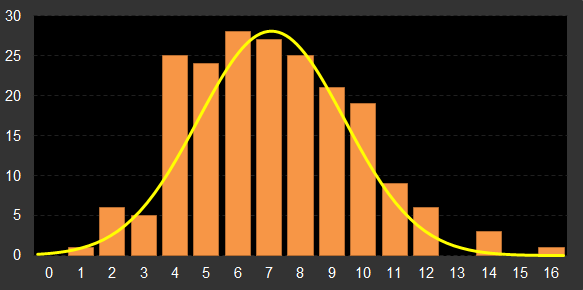

The average (mean) aquamanile size is 28L x 26H x 13W centimeters. The smallest recorded aquamanile is in the form of a lion in Hildesheim and is a mere 16L x 16H. It is damaged and therefore lacks 1-2 centimeters of height. The largest is a massive 38L x 43H centaur in Budapest. Figure 4 shows the size distribution of the aquamanile sample documented on this website. A heuristic derived from the length and height dimensions places each aquamanile into a size category, 0 through 16. The extreme ends are marked by the two aquamanile previously mentioned. Size category 7 contains the mean. Aquamanilia size are approximately normally distributed. The notable exception is a dramatic step up from size category 3 to 4. A hypothesis is that it represents a usability threshold. A useful aquamanile must be able to hold enough water for several hand washings. Size category 4 aquamaniles probably fulfill this requirement. Those smaller are novelties. Likewise, as size grows, the item becomes unwieldy and serves only as a sign of opulence.

Production Centers

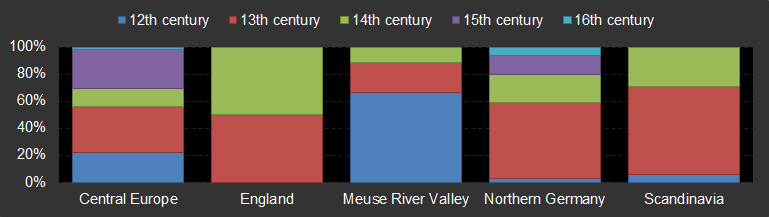

Early aquamanile production of the 12th century took place largely in the Meuse river valley, and drew inspiration from an art style known today as Mosan. The Meuse river stretches from the north of France, through Belgium, and terminates in the river deltas surrounding Rotterdam, finally draining into the English Channel. In the 13th century, aquamanilia were being produced not only in the Meuse river valley, but also in northern Germany, an area that was becoming famous for its metal work. Hildesheim was likely the largest production center in northern Germany. Located in the region, the Brunswick (Braunschweig) Lion, a massive 12th century bronze casting, is a forerunner of a style that was propagated through aquamanilia for the next three centuries. By the 14th century, the prominence of the Meuse river valley production centers had faded, and those in northern Germany and even Scandinavia and England controlled the market. Hans Apengeter, an influential 14th century north German metal caster, is thought to have contributed to aquamanile designs. His followers likely produced many aquamanilia. As the 14th century came to a close, Nuremberg emerged as a production center, creating ever more complicated designs. Finally, production after the late middle ages took place in Brunswick, the very birthplace of medieval German casting. The map, figure 6, depicts all documented production centers. Region boundaries are approximate. There were probably only a few workshops within each region.

Reproductions

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, with a newfound interest in things medieval, a number of aquamanilia were produced, some passed off as originals and others explicitly reproductions, even repurposed.

The most common copy is based on an original in the form of a lion at the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg. The museum sold plaster casts of the aquamanile ostensibly for educational purposes sometime after 1850. From these casts, more than 20 different copies in 3 different sizes and with varying functionality were created. A number of the best of these reproductions are in the hands of museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the British Museum in London, and the Museo Lázaro Galdiano in Madrid. The German company Erhard & Söhne, based in southern Germany, produced numerous copies that functioned as oil lamps and lighters. The C. W. Fleischmann company in Munich made copies of five different aquamanilia from the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg, and one from the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum in Munich, amongst other copies of medieval castings (Figure 7). The Otto Hägemann company in Hanover also made copies of an aquamanile. There is at least one modern original design sometimes seen at auction.

Fakes are a second class of modern aquamanilia. Despite not being medieval, these are mostly held in museum collections and their true natures acknowledged. Among these fakes are aquamanilia in the shape of a head, and four lions, one seated. Both head aquamanilia are held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and are believed to be 19th century original designs. A lion held by the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore is cast from the original held at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Another lion from the Halberstadt Cathedral collection was copied at least twice, one held by the V&A and one passing through an auction house. A third lion from the Bayerisches Nationalmuseum also has two copies, one held by the Museum für Angewandte Kunst Frankfurt and the other at the National Museum in Prague. Finally, the seated lion at the Metropolitan Museum of Art is modern and closely resembles another at the Museen für Kunst und Gewerbe in Hamburg. At least a dozen other copies of four other aquamanilia exist, plus modern original designs passed off as medieval.